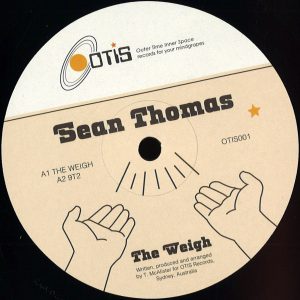

Our very own Thomas McAlister has devoted much of his studio time exploring a deeper, more brooding side of club music with his projects Cop Envy and Alba. Earlier this year, he unveiled a new production moniker, Sean Thomas, with an EP release on local label OTIS records. The four tracks sit in a moody yet upbeat pocket, informed by early deep house and drum and bass. We took a brief time out in the Liveschool kitchen to discuss the influences and production behind the release.

You’ve mentioned that these tracks were done in a short timeframe with a pretty specific goal. Want to just run me through what your aim was with these tracks and what the writing process was like?

Basically, as I sometimes do, I was obsessing over this particular breed of house music, that was partly in my head and partly already in existence. I was on a YouTube binge trying to find tracks that fit this style, and as I was doing it, I was pulling a bunch of samples straight from the YouTube videos. I guess at some stage it finally clicked as to what I was looking for, and I felt like I could jump in and pull off the sound myself.

The writing process was very quick and dirty. I used a single project for all songs, and made about 5 rough sketches in an afternoon. I didn’t have ambitious plans for the tracks, I was really just experimenting with trying to make music that fit this mould that I had come up with.

The writing process was very quick and dirty. I used a single project for all songs, and made about 5 rough sketches in an afternoon. I didn’t have ambitious plans for the tracks, I was really just experimenting with trying to make music that fit this mould that I had come up with.

The music is primarily made up of very stock drum sounds, the samples I had been recording from youtube at the time, and samples from youtube and records that I had already collected. The only ‘traditionally composed parts’ are the basslines on all but one track and two other melodies.

What ideas or hallmarks piqued your interest when you were sampling? What were you taking and applying to your own tracks?

It sounds a little corny, but the mould was mainly a kind of mood. I was going for house music that felt particularly deep and heavy, but not in a sinister way at all. While the process was very sample-heavy, I wasn’t interested in making house music that sounded that way. it’s kind of ironic really, that one of the main things I was thinking about was making music that sounded very synth-heavy, but largely used samples to create that.

The two big references were this certain strain of Detroit-obsessed UK house music and classic jungle / deep drum and bass. I felt there was a really common strain between those styles that I wanted to sit in. The commonalities being big digital 90s synth sounds, heavy sub content, and a very late night and deep mood while still being very danceable and energetic.

Were you considering these tracks as bridging tools for sets touching on those two areas at all?

Hmmm good question. Not necessarily, but maybe subconsciously. I was thinking very little about how these tracks would end up being used, but I definitely had in the back of my mind the kinds of club environments the tracks would suit.

What sort of clubs?

The ones I dream of.

What’s your dream club?

Well I guess I was thinking of those sets where the music is never totally too far down one path. Where you don’t walk out thinking ‘hey they just nailed that disco set,’ where there is a common mood rather than style.

It seems like you’ve cherry picked the ideas from your house and junglist leanings that feel cohesive when brought together in the one arrangement.

You got it. A lot of the samples are from jungle tunes, especially the pads. There have never been deeper pads than there were back then.

Working out of the one project in Live seems like a nice way to share ideas through multiple tracks. Do you often work like this?

Definitely, more so in recent times. Even for Cop Envy tunes I’ll usually squeeze at least two ideas out of any given project.

Why do you like it?

I mean I guess it’s economical. Already having developed a nice palette, it feels like a waste not try get more out of it. It’s a surefire way to achieve consistency across tracks. With a good squad of hardware, consistency is very easily achievable. I guess setting up systems and running with them in a software environment brings similar results

The OTIS website gives a shout out the Phono / Red Ember labels as big influences for this release. Any tracks out of their catalogues that are stand outs to you?

Strange Attractor – Golden Gate / Luxor: Definitely an influencer on the Sean Thomas tracks. Luxor is worryingly heavy.

Ewan Jansen – Midnight Motion: Not sure if it was ever actually released on Red Ember, but to me it is dripping in jungle textures, but is very much house music. so it definitely fits that ‘mould’.

How did the OTIS release come about?

So the day I made the tracks, I stuck them on Soundcloud under the Sean Thomas alias, just to kind of see what would happen, and to stop myself from letting them just sit on my hard drive for ever. Then Hugh (OTIS Records) came across them and asked if I would be interested in releasing them. His tastes for the label seemed very much in line with what I was trying to achieve with the tracks so it was serendipitous.

Do you let go of tracks like this often or are you more of a hard drive forever kind of person? Would you recommend the sharing process?

There’s definitely a tonne of hard drive forever tracks, but probably for good reason. However I guess I do recommend the sharing process, it’s cathartic. Both the Sean Thomas and Cop Envy projects came about by just putting the tracks online and seeing what would happen.

So if you’re working in the same Live project, what are some of the moves that you’re pulling to streamline your workflow / get that consistency of sound? Is it purely using the same samples or does it go deeper with processing in similar ways?

It’s a mixture of using the same samples and same processing. I generally will use a sampler of some description for all the samples I am using, and this means I can pretty much just grab all the clips in my project and delete them, then attempt to compose completely new material using the same source material and processing, and only adjust or apply new material or processing as needed.

For these tracks I was doing a lot more master buss processing than I otherwise would, and since then have applied those processes to a lot of my tracks outside of the Sean Thomas work. Standard stuff like compression and saturation, but just a little more heavy handed than I would usually be. And then more ‘non standard’ stuff, a pitch shifter on the master is something I used a lot of.

Ha! What for?

It just adds some strange artefacts to the overall mix. I guess its just another way to glue things together, given its on the master track, its adding these artefacts and harmonics across the whole mix. Sometimes pitch shifting up a certain amount, and then back down by the same amount so the key isn’t compromised, but you’re still getting those odd textures popping out.

You’d want to be pretty judicious with any serious master bus processing though right?

I guess given its largely music designed for the club, I’d just be making sure it doesn’t compromise the low end too much, which things like pitch shifters can definitely mess with. With the ‘no shift’ technique (pitching up then down by the same amount), you can apply it to only a certain band of frequencies and leave the low alone.

What’s next for Sean T?

Nothing solid on the horizon, make some more tracks, do some more records!

Thom is a trainer for the Create, Destroy, and Sound Design modules of our Produce Music course. To find out more about our upcoming intakes, click here.